One Docker Bake Pipeline to Rule Them All - Part I: The Baking

If you’ve ever maintained CI/CD pipelines for Docker images, you know how fast they get out of hand. A new service? A new workflow. A new architecture to support? Another workflow, or a painful retrofit of the existing one. Before long you’re maintaining five pipelines that all do roughly the same thing in slightly different ways, and every time one of them breaks you have to remember which quirks belong to which.

This series is about building a single reusable GitHub Actions pipeline that handles all of it. One pipeline, any number of targets, any mix of architectures. In Part I we build the foundation: the baking. In future parts we’ll layer on security scanning and whatever else the pipeline needs to do before an image earns its place in a production cluster.

The code for this part can be found in this PR: https://github.com/k-candidate/gha-workflows/pull/3.

Why docker bake?

Docker has two ways to build images. docker build builds one image at a time. You specify a Dockerfile, a context, some args, and you get an image. It’s imperative: you tell it exactly what to do, step by step.

docker buildx bake is the declarative alternative. You write an HCL file that describes what you want: which images, what tags, what platforms, what build args. Bake figures out how to do it. The bake file is checked into your repo. It’s the source of truth.

This distinction matters for a reusable pipeline. If the pipeline is built around docker build, it has to know how to orchestrate every detail: which Dockerfiles exist, what to name the images, what platforms each one supports. That knowledge lives in the pipeline, and every repo that uses it is constrained by it. With bake, that knowledge lives in the repo’s own bake file. The pipeline just reads it and acts on it.

This also draws a clear line between two teams. The DevSecOps team owns the pipeline: they maintain it, they extend it, they make sure it stays secure and reliable. The SWEs own the Dockerfile and the bake file: they define what gets built and how.

The problem we’re solving

Building multi-platform Docker images in CI is trickier than it looks. You can’t just run docker buildx bake and get a multi-platform image out the other end, at least not reliably, and not with the performance you want. Here’s why:

Building an ARM image on an AMD64 runner works via QEMU emulation, but it’s slow. Significantly slower than building natively on an ARM runner. For a serious pipeline, you want each architecture built on its native hardware.

But GitHub Actions matrix strategies, the mechanism you’d use to parallelize builds across runners, require you to know your build matrix at workflow definition time. You can’t dynamically say “this target needs amd64 and arm64, that one only needs amd64” unless something first reads the bake file and produces that matrix.

And once you’ve built platform-specific images separately, you need to stitch them back together into a manifest list. That’s the thing that makes a single tag like myregistry/myapp:latest serve the right image to the right architecture automatically.

So the pipeline has three distinct phases, and they can’t be collapsed: discover what to build, build it in parallel on the right runners, then assemble the results.

A deliberate choice: no remote builders, no custom networking

Before we get into how the pipeline works, it’s worth explaining something about how it doesn’t work, and why.

One of the approaches to multi-platform builds in CI involves remote buildkit endpoints. See https://docs.docker.com/build/ci/github-actions/configure-builder/#append-additional-nodes-to-the-builder for more information. You set up a buildx builder that connects to remote machines over TCP, each one handling a different architecture. This looks something like: https://github.com/docker/packaging/blob/2c95ad0ca93ea91a01755b01e9a979adec955540/.github/workflows/.release.yml#L62-L89

- name: Set up remote builders

uses: docker/setup-buildx-action@v3

with:

driver: remote

endpoint: docker-container://buildx_buildkit_${{ steps.buildx.outputs.name }}0

append: |

- name: aws_graviton2

endpoint: tcp://${{ secrets.AWS_ARM64_HOST }}:1234

platforms: linux/arm64,linux/arm/v7

- name: linuxone_s390x

endpoint: tcp://${{ secrets.LINUXONE_S390X_HOST }}:1234

platforms: linux/s390x

env:

BUILDER_NODE_1_AUTH_TLS_CACERT: ${{ secrets.AWS_ARM64_CACERT }}

BUILDER_NODE_1_AUTH_TLS_CERT: ${{ secrets.AWS_ARM64_CERT }}

BUILDER_NODE_1_AUTH_TLS_KEY: ${{ secrets.AWS_ARM64_KEY }}

BUILDER_NODE_2_AUTH_TLS_CACERT: ${{ secrets.LINUXONE_S390X_CACERT }}

BUILDER_NODE_2_AUTH_TLS_CERT: ${{ secrets.LINUXONE_S390X_CERT }}

BUILDER_NODE_2_AUTH_TLS_KEY: ${{ secrets.LINUXONE_S390X_KEY }}

Look at what this requires. TLS certificates for every remote builder. Secrets for every node. TCP endpoints that the CI runner must be able to reach. Custom networking that works in your environment but may not work in someone else’s. If you run this on GitHub-hosted runners, you have zero control over the network. If you run it on self-hosted runners, you have to maintain all of it.

I chose a different path. Instead of connecting one runner to remote builders over the network, I let GitHub Actions do what it does best: run jobs on different kinds of runners natively. ARM builds run on ARM runners. AMD64 builds run on AMD64 runners. Each runner only needs to reach the container registry over standard HTTPS, which works everywhere, on GitHub-hosted runners and on self-hosted runners alike. No remote endpoints. No TLS certificate management. No custom networking. The pipeline is portable by design.

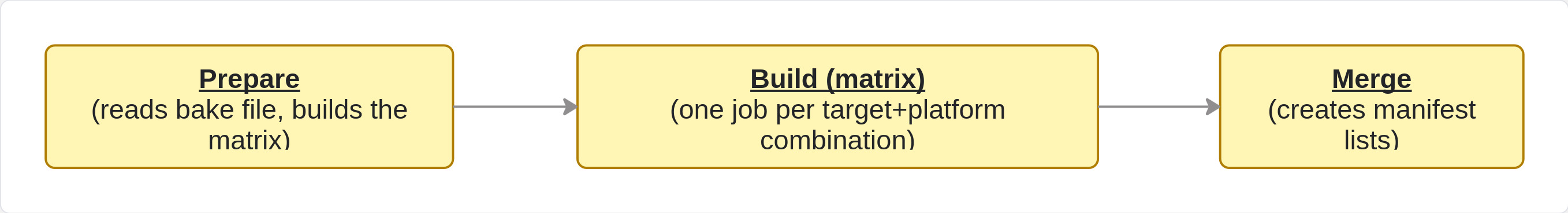

The architecture: three jobs

Job 1: prepare

This job runs docker buildx bake --print, which parses the HCL and dumps the resolved configuration as JSON without actually building anything. From that JSON it produces everything the rest of the pipeline needs:

The build matrix: a list of {target, platform} pairs. If your bake file has three targets and two of them support both amd64 and arm64 while the third only supports amd64, the matrix has five entries. Five parallel build jobs, automatically. Add a new target or a new platform to the bake file and the matrix grows with it. No one touches the pipeline.

The targets info: for each target, its final tags and its platform list. The merge job needs this later to know which digests to stitch together under which tags.

A needs_merge flag: true if any target has more than one platform, false otherwise. If everything is single-platform, the merge job is skipped entirely. There’s nothing to merge.

An instance ID: a random hex string that namespaces all artifacts produced by this invocation. This is what makes the pipeline safe to call multiple times in the same workflow run without artifact name collisions. More on that below.

Job 2: build

This fans out from the matrix. Each job builds exactly one target for exactly one platform, on the right kind of runner: ARM targets go to ARM runners, AMD64 targets go to AMD64 runners. Native builds, no emulation. The runner types are configurable inputs with sensible defaults, so teams using self-hosted runners can point the pipeline at their own fleet without any code changes.

Each job pushes its image immediately after building. It doesn’t hand off a local image to some later step. It pushes to the registry and captures the digest that comes back. A digest is the content-addressable identifier of that specific image in the registry. It’s what you need to reference a platform-specific image when assembling a manifest list.

That digest gets saved as an artifact. The naming scheme encodes everything the merge job will need to find it: the instance ID, the target name, and the platform.

Job 3: merge

This job downloads all the digest artifacts, then loops over every target. For targets with multiple platforms, it creates a manifest list: a single tag that points to all the platform-specific images. docker buildx imagetools create does this. It takes a list of tag@sha256:digest references and produces a manifest list under a new tag.

For targets with only one platform, it does nothing. The image was already pushed with all its tags during the build step.

At the end, it inspects every tag it created. This is the verification step. It’s how you confirm in the pipeline logs that the manifest lists contain the platforms you expect.

How callers use it

Here’s what I am using to test the pipeline: https://github.com/k-candidate/gha-test/blob/bbaad8353ded606e3d85c70b6798520cb463f0d7/.github/workflows/test-docker-bake.yaml.

The pipeline is a reusable workflow (workflow_call). Using it looks like this:

jobs:

build:

uses: your-org/shared-workflows/.github/workflows/docker-bake.yaml@main

secrets:

dockerhub_username: ${{ secrets.DOCKERHUB_USER }}

dockerhub_token: ${{ secrets.DOCKERHUB_TOKEN }}

with:

bake-file: ./docker-bake.hcl

version: ${{ github.ref_name }}

That’s it. The caller provides a bake file and credentials. Everything else has sensible defaults. This is where the shared responsibility model pays off in practice. The developer doesn’t need to understand how the pipeline orchestrates builds across runners or assembles manifest lists. They write a bake file, point the pipeline at it, and it works. The DevSecOps team can update the pipeline internals, add scanning steps, change how digests are handled, and none of that touches the caller’s workflow or their bake file.

The version input deserves a closer look. It’s how repos tag their images from releases without hardcoding version strings into the bake file. The bake file declares a variable and uses it in tags:

variable "VERSION" {

default = "unknown"

}

target "myapp" {

tags = [

"myregistry/myapp:${VERSION}",

"myregistry/myapp:latest"

]

platforms = ["linux/amd64", "linux/arm64"]

}

The pipeline exposes the version input as a VERSION environment variable when it runs bake. Bake natively picks up environment variables that match declared variable names. So ${VERSION} resolves to whatever the caller passed in: a release tag, a commit SHA, anything. No special plumbing needed.

The details that matter

A few design decisions in this pipeline are worth understanding, because they solve problems you’ll hit if you try to build something like this from scratch.

Why not just run bake once and let it handle everything? Because bake can’t natively distribute builds across different runner types. It can build for multiple platforms, but it does so on a single runner, which means QEMU for any architecture that doesn’t match the runner. The pipeline decomposes what bake declares into individual jobs that each run on the right hardware, then reassembles the results.

Why push during build instead of collecting images locally? All roads to Rome. Pushing immediately means each build job is self-contained: it builds, pushes, captures the digest, and it’s done. The merge job doesn’t move images around. It just creates a manifest list that points to images that are already in the registry. This is also what keeps the networking requirements minimal. Each runner only needs outbound HTTPS to the registry. No runner-to-runner communication, no shared volumes, no local registry to coordinate.

Why the instance ID? GitHub Actions artifact names must be unique across an entire workflow run, not just within a job. If two caller jobs invoke this pipeline simultaneously and both build a target called myapp for linux/amd64, their artifact names would collide. The instance ID is generated independently by each invocation’s prepare job and prefixed onto every artifact name. The caller doesn’t need to know it exists.

Why skip merge entirely for single-platform builds? A manifest list is specifically the mechanism for serving different images to different platforms under one tag. If there’s only one platform, there’s nothing to multiplex. The image is already tagged correctly. Running merge would be an empty loop on an unnecessary runner.

Why fail-fast: false? If one target fails to build, the others should still complete. You want to see the full picture of what passed and what failed, not have the entire pipeline abort on the first failure.

Who owns what

This pipeline is designed around a shared responsibility model.

The DevSecOps team owns the pipeline itself. They maintain it, extend it, and make sure it stays reliable and secure. When new capabilities are added to the pipeline, whether that’s vulnerability scanning, image signing, or anything else, that work happens entirely inside the pipeline. No developer has to change their workflow or their bake file.

The developers own the Dockerfile and the bake file. They decide what images to build, what platforms to target, what tags to use, and what the build context looks like. They don’t need to understand how the pipeline orchestrates builds across runners or assembles manifest lists. They just need to know the contract: write a bake file, call the pipeline, get images in the registry.

This separation is what makes the pipeline reusable across an organization. Every team gets the same build infrastructure, the same security gates, the same reliability. They just bring their own bake files.

What’s next

This pipeline builds and pushes images. It doesn’t yet say anything about whether those images are safe to deploy. In the next parts we’ll add vulnerability scanning, signing, and the other gates that should stand between a build and a production cluster.

This isn’t an afterthought. Security was part of the design from the start. The three-job architecture, the clean boundaries between prepare, build, and merge, the fact that each phase communicates through well-defined outputs and artifacts. All of it was built with extensibility in mind. Each phase is a separate job with a clear boundary. Adding a scanning step means adding a job. It doesn’t mean rewriting the ones that already exist.